EFL

university teachers’ perceptions of writing assessment training

Percepciones de Docentes Universitarios sobre un Taller de

Evaluación de Escritura en

Inglés como Lengua Extranjera

Elsa Fernanda González[1]

ABSTRACT

Assessment literacy is a term that

has arisen from the worldwide constant use of assessment data and the need to

help teachers understand and apply assessment procedures in their language

classrooms (Malone, 2013; Inbar-Lourie, 2013). It

involves the theoretical knowledge of assessment, its principles and the know

how to (Fulcher, 2012) apply them in each specific context. Specifically, the

assessment of writing remains a difficult activity that English as a Foreign

Language (EFL) Mexican teachers are required to conduct as a regular activity

of their language teaching profession. However, these activities are carried

out, most of the times, without the proper training, guidance and consideration

of teachers’ needs to assure students’ assessment validity and reliability. The

study explores the perceptions that 48 Mexican EFL university teachers had in

relation to the effectiveness of two writing assessment training sessions provided

to them in a period of twelve months. Data obtained from a background questionnaire

and an online post training questionnaire suggested that half of the teacher

participants did not have previous writing assessment training nor for the use

of scoring tools such as analytic and holistic rubrics. Additionally, it was found

that although teachers found the sessions useful and practical for their future

assessment practice they considered more practice using assessment rubrics and

understanding the writing assessment process was needed. Teachers’ perceptions

are also analyzed regarding the perceived changes that training encouraged. It

is concluded that the inexperience with writing assessment that most of the

teachers stated to have may have influenced the perceptions participants

reported. Implications for the language student, teacher and institution are

discussed in the conclusions of the paper.

Palabras clave: assessment

literacy, EFL writing assessment, EFL teachers, teacher training, scoring

rubrics.

RESUMEN

La alfabetización de evaluación es un término que ha surgido

del uso constante en el ámbito internacional de los datos de evaluación y la

necesidad de ayudar a los maestros a comprender y aplicar los procedimientos de

evaluación en sus aulas de idiomas (Malone, 2013; Inbar-Lourie,

2013). Implica el conocimiento teórico de la evaluación, sus principios y el

saber hacer (Fulcher, 2012) que se aplican en cada

contexto específico. Específicamente, la evaluación de la escritura sigue

siendo una actividad difícil que los profesores mexicanos de inglés como idioma

extranjero (EFL) deben realizar como una actividad regular de su profesión de

enseñanza de idiomas. Sin embargo, estas actividades se llevan a cabo, la

mayoría de las veces, sin la capacitación, orientación y consideración adecuada

de las necesidades de los maestro para asegurar la validez y confiabilidad de

la evaluación de los estudiantes. Considerando esta problemática, el presente estudio

explora las percepciones que 48 profesores universitarios mexicanos de inglés como

lengua extranjera tenían en relación a la efectividad de dos sesiones de

capacitación de la evaluación de escritura que se les brindaron en un período de doce meses. Los datos obtenidos de

un cuestionario de antecedentes y un cuestionario electrónico posterior a la

capacitación sugirieron que la mitad de los docentes participantes no tenían

una capacitación previa en evaluación de escritura ni para el uso de

herramientas de evaluación como las rúbricas analíticas y holísticas. Además,

se encontró que a pesar de que los profesores consideraban que las sesiones eran

útiles y prácticas para su futura práctica de evaluación, consideraban que era

necesario comprender el proceso de evaluación de la escritura. Las percepciones

de los maestros también se analizan con respecto a los cambios percibidos que

la capacitación alentó. Se concluye que la inexperiencia con la evaluación de

la escritura que la mayoría de los maestros tenia pudo haber influido en las

percepciones manifestadas por los participantes. Las implicaciones para el estudiante de idiomas,

el maestro y la institución se discuten en las conclusiones del presente

estudio.

Keywords: alfabetización evaluativa, evaluación de la escritura

en inglés como lengua extranjera, docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera, capacitación

docente, rubricas de evaluación.

INTRODUCTION

In many higher education institutions of Mexico, English

as Foreign Language (EFL) teachers are required to teach and assess the four

language skills on a regular basis. They need to select an assessment method;

develop the assessment tool or use one provided by the program manager;

administer and score the tool; interpret and make decisions related to the

score; communicate the results and cope with the consequences that assessment

and evaluation may have (Crusan, 2014; Fulcher, 2012;

Stoynoff and Coomb, 2012; Weigle, 2007). To perform all these activities university

language teachers need to be assessment literate.

The lack of assessment literacy may not only result

in a heavier workload for teachers; it may also negatively affect the validity

and reliability of the assessment of their students’ writing abilities.

To develop writing assessment literacy teachers

require continuous, well-planned training. Lack of training often results in

teachers’ uneasiness and distrust in their abilities to assess their students’

written work (González, 2017). Training may favor score and assessment

reliability and consistency (Bachman and Palmer, 2010; Hamp-Lyons, 2003; Weigle, 2007). Teachers, however, might not value the

training received, or their views of training may impede a positive impact on

their assessment practices. Teachers’ perceptions of writing assessment

training are therefore, a legitimate field of inquiry.

Assessment literacy means being familiar with and using

measurement practices to assess the language used by students for a class (Malone,

2013). Assessment literacy research began in the late 1990s and it has

investigated writing teachers’ assessment training needs; teachers’ perceptions

of assessment training; and the impact of trainers’ backgrounds on the content

and procedures of the assessment training they provide (Bailey and Brown, 1996,

2008; Fulcher, 2012; Hasselgreen and col. 2004; Jeong, 2013; Nier and col. 2013; Stiggins,

1995). Studies on assessment literacy take place in classrooms of English as a

first language (L1), English as a second language (ESL), and English as a

foreign language (EFL). Studies that examine assessment training in ESL and EFL

contexts, focus mainly on the impact of raters’ training; raters’ backgrounds;

raters’ use of rubrics; raters’ gender and other issues of large-scale testing

(Barkaoui, 2007, 2011; Eckes,

2008; Esfandiari and Myford,

2013; Lim, 2011).

Specifically in EFL education, Nier

and col. (2013), focused on analyzing a blended learning assessment course and

its usefulness to participants. They administered a post-training questionnaire

to 35 teachers and analyzed the group discussions conducted during the face-to-face

encounters. Results indicate that most participants considered the blended

learning approach as useful, but required more examples to understand the

processes of assessment. Participants identified the course and mode of course

as a helpful and useful mode of professional development.

In another study, Jeong

(2013) examined teacher trainers’ understanding of assessment and the ways in

which their assessment background influenced the outcomes of their assessment

courses. Participants were 140 instructors of language assessment courses (both

language testers and non-language testers).

Data were collected with the use of an online survey and a telephone

interview. Findings show that there were significant differences in the content

of the courses depending on the instructors’ background in six topic areas:

test specifications, test theory, basic statistics, classroom assessment,

rubric development, and test accommodation. Non-language testers were less

confident in teaching technical assessment skills compared to language testers

and had a tendency to focus more on classroom assessment issues. The researcher

recommends language testers to share their knowledge and make it accessible to

those who are part of the language assessment community. Research still needs

to explore the writing assessment literacy of EFL teachers; the ways in which

EFL teachers assess writing; and the impact of EFL teachers’ perspectives of

assessment on their assessment practices. Research should also explore the

assessment context, the assessment needs, and the perceptions of assessment

training of EFL teachers in Latin American countries.

In Mexico, undergraduate students in most universities

are required at least a B1 level of proficiency in a language other than

Spanish. Therefore, teachers need to be assessment knowledgeable; have

practical assessment skills; have the capacity to connect classroom assessment

to large-scale tests; and maintain the focus on students’ learning as the main

purpose of assessment. Assessment literacy is particularly important to develop

the complex ability of EFL writing.

This study examined the perceptions of teachers that

participated in a two-session writing assessment workshop in the 2014-2015

school calendar. The research questions addressed were the following:

1) What are the teachers’ perceptions of the

usefulness of the writing assessment training received?

2) How do writing assessment training

influence classroom assessment practices?

METHODOLOGY

This study uses a cross-sectional, non-experimental,

intervention design. It is descriptive and exploratory. It does not intend to

generalize the results to other populations. Instead, its purpose is to analyze

the unique traits that characterize the small group of participants. Data

collection and analysis were driven by a mixed-methods approach. Combining

quantitative and qualitative data allowed a better understanding of the

teachers’ perceptions of assessment and the assessment training they received

(Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Creswell, 2013). In an effort to care for the

validity and reliability of the findings

here portrayed data was shared with an experienced researcher in the

area of applied linguistics following a peer checking process (Dörnyei, 2007) that allowed the comparison of results obtained

from both researchers. To diminish the Hawthorne Effect as well as the Social

Desirability Bias (Dörnyei, 2007) effect a data triangulation

method was conducted during which specific data was elicited in different forms

and structures within the same online questionnaire.

Participants and research context

Participants were teachers of three universities (19

participants) and one language institute (29 participants) in the northeastern

corner of Mexico. Initially, 150 teachers were invited to take part in the study,

since they were in service teachers at the time of the study, and teaching in

university settings. However, only 48 gave their informed consent to

participate. A convenience sampling method was used (Dörnyei,

2007) which emphasizes the inclusion of those participants who were available and

willing to take part in the study.

The teachers’ institutions of affiliation used different

programs and methods to teach and assess writing. Regarding their assessment policies,

all four schools required their teachers to calculate a holistic score (0-10 or

0-100) that integrated students’ EFL writing proficiency with other language

skills. Teachers from the language institute reported that the institution had

established writing tasks and scoring rubrics to assess the writing abilities

of students. University teachers, on the other hand, stated that their

institutions did not provide assessment guidelines and they were free to decide

on their assessment approaches. Neither the language institute nor the universities

gave their teachers EFL writing assessment training.

Writing assessment training

The researcher, who was also the trainer, delivered

the workshop in two sessions. The first session focused on the nature of EFL

writing, writing assessment, and the use of holistic and analytic rubrics. The

second session focused on the importance of using rubrics to assess writing

skills and giving trainees time for practice. Teachers reflected on the

characteristics of their teaching contexts and their assessment practices. The

trainer structured the workshop in accordance with the concept of “assessing

for learning” (Stiggins, 1995); the manual for language

examinations (Concil of Europe, 2002; 2009a; 2009b)

of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR); and the manual for

language test development and examining (2011) of the Association of Language

Testers in Europe (ALTE). The assessment training given to participants included:

(a) guided discussion of previously scored samples; (b) independent marking and

follow-up discussion of scores; and (c) independent marking and pair discussion

of scores.

Data collection instruments

Two data collection instruments were used: a

background questionnaire and an online post-training questionnaire. The

background questionnaire was paper-based and administered on-site during the

first training session. It gathered information about the participants’ EFL

teaching and assessment experience.

A combination of eight multiple-choice and three open-ended

questions were included in the background questionnaire to provide informants

with opportunities for free expression (Nunan, 1992).

The post-training questionnaire was written in the participants’ L1 (Spanish)

and delivered electronically with the use of a survey generation and research

platform for members of the University of Southampton (found at: https://www.isurvey.soton.ac.uk/). The

tool made thedata collection processes effective for

the researcher and attractive for the participants (Dörnyei

& Taguchi, 2010). The survey included Likert-scale items, closed and open

questions (Dörnyei, 2007). It was pilot tested (Dörnyei,

2003) with a group of EFL teachers that were not part of this study.

Data collection and analysis procedures

Data collection for the study involved two stages in

a period of twelve months. In the first stage, the researcher asked

participants to complete the background questionnaire and delivered the first

training session, which lasted approximately three hours which included a

20-minute break. Eight months later, in stage two, the researcher provided the

second assessment training session, which took approximately two to three hours

to complete. During the session teachers engaged in assessment practice with

scoring rubrics, group discussion and benchmark scoring of sample papers. They

also shared their reflections on the changes they had observed in their assessment

practice, after receiving the first assessment training session. Then, the

researcher explained how to answer the online post-training questionnaire and

notified teachers they would receive a link by email to answer it. Teachers

answered the questionnaire two to three weeks after completing the second

training session.

For the analysis, descriptive statistics was used with

data that came from the closed-ended items of both questionnaires. The

information was introduced into the Statistical Package for the Social

Sciences (SPSS. 23) to calculate Means, Mode, and frequency of data items. The

sample of teachers did not allow for inferential statistics analysis and

therefore, only exploratory and descriptive statistics were used.

For the analysis of open-ended questions, themes were

identified and clustered into categories. Each category was given a code and

frequencies for each code were calculated (Creswell, 2015).Participants’

responses were analyzed in Spanish to avoid translation of data bias or

subjectivity (Pavlenko, 2007). Once the analysis

ended, responses were translated into English to report the results.

RESULTS

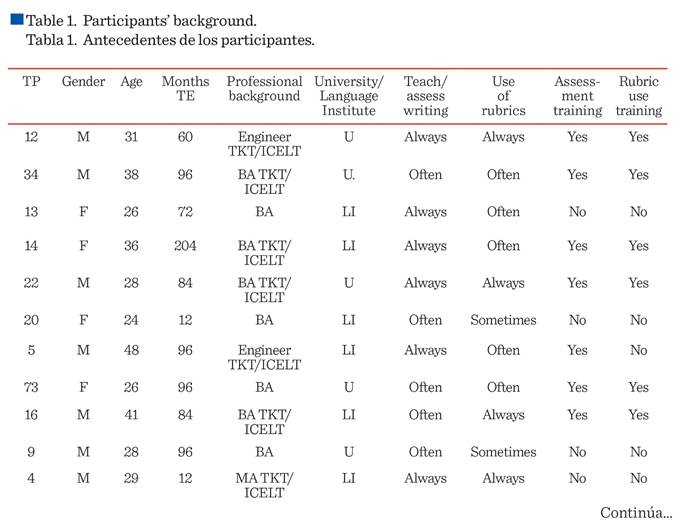

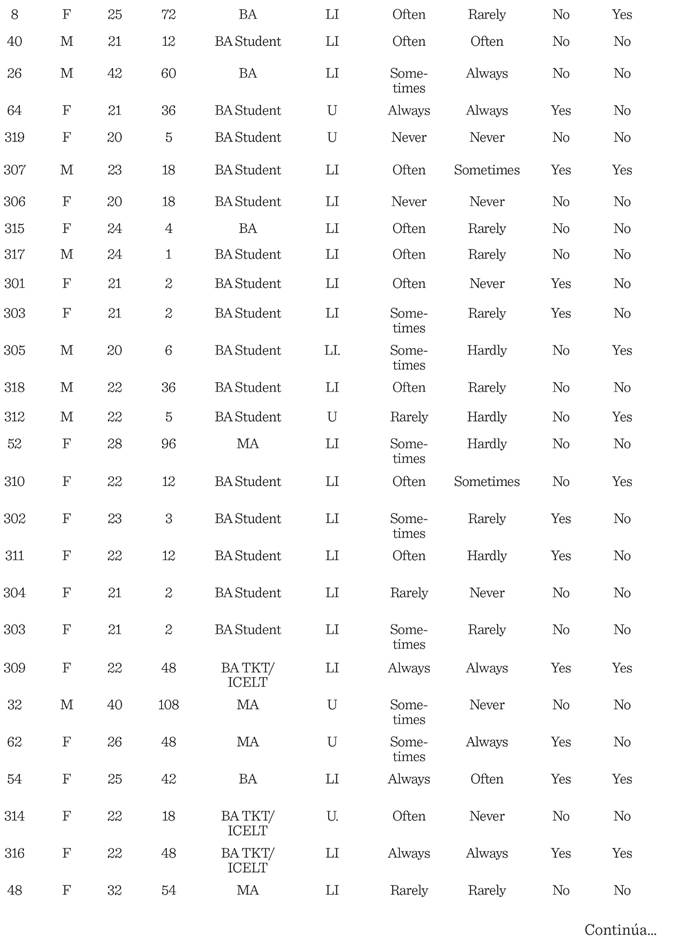

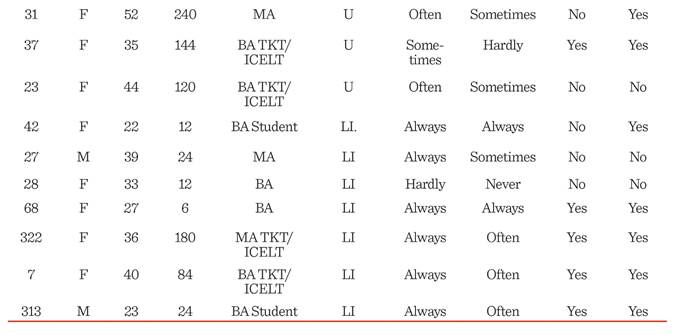

Participants’ background Participants were 65 % female

and 35 % male EFL teachers. Their ages ranged from 20 to 52 years. Regarding

their teaching experience, 67 % had taught for five or less years; 25 % had

five to nine years of experience; and only 8 % had been teachers for 10 or more

years. As to their professional

background, 38 % were undergraduate students working as English language

teachers; 29 % had under- graduate or graduate degree and a teaching certificate

(Teaching Knowledge Test or the In-Service Certificate of Language Teaching by

Cambridge English Language Assessment). Finally, 33 % of the trainees had undergraduate

or graduate degree and lacked a teaching certificate. Information on the

participants’ background is shown on Table 1.

To compare the participants’ assessment practices

before and after the training, the background questionnaire investigated their previous

assessment training and use of assessment tools. As shown on Table 1 above, 54

% of the participants responded that they had not received assessment training,

while 46 % answered that they had received assessment preparation. Trainees also

reported the assessment frequency in their teaching of EFL writing. Of the 48

teachers, 36 % reported that they often assessed writing; 34 % responded that

they assessed writing always. Together, people that often and always assessed

writing, made 70 % of the sample. However, 20 % sometimes assessed their

students; 5 % never did; and 5 % rarely assessed writing in their classrooms.

In relation to assessment tools, teachers were asked

about their rubric training and rubric use. Table 1 shows that 56 % responded

that they had never received training and 44 % stated that they had received

preparation in the use of assessment tools. This is consistent with 44 % of the

teachers that informed that they used rubrics (23 % stated that they always

used rubrics and 21 % responded that they often did), and 56 % that reported an

infrequent use of rubrics (17 %, rarely; 15 %, sometimes; 15 %, never; and 9 %,

hardly ever).

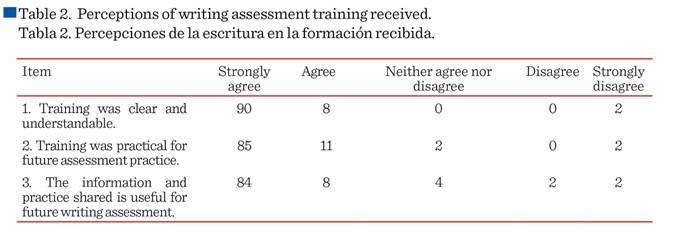

What are the teachers’ perceptions of the writing

assessment training received? In general, the EFL writing assessment workshop

was well accepted by the trainees. Most of them (90 %) considered that the

content was clear and understandable. A high percentage of them (96 %) either

agreed or strongly agreed with the idea that the training was practical in

their subsequent assessment practice. The

majority of them (92 %) agreed or strongly agreed with the item that read: The

information and practice shared is useful for future writing assessment. These

results are shown on Table 2.

How do writing assessment training

influence classroom assessment practices?

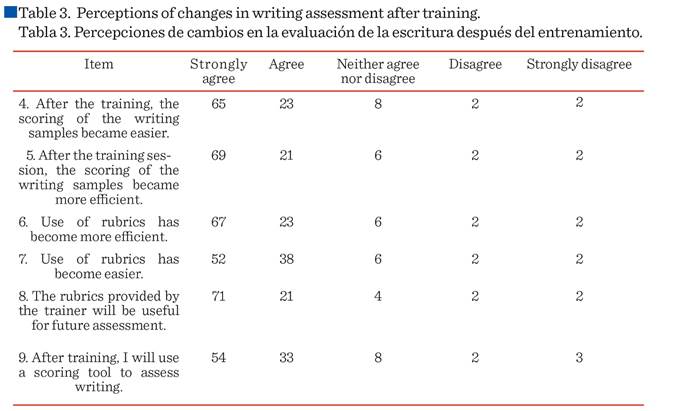

As can be portrayed on Table 3, the

he teachers’ perception of the influence of the training on their assessment

practice was generally positive. A large group (88 %) agreed or strongly agreed

with the notion that scoring their students’ pieces of writing became easier

for them after the workshop. Many of them also perceived that scoring (90 %)

and the use of rubrics (90 %) became more efficient.

The use of rubrics became easier

(90 %) and so they considered that the rubrics provided by the trainer during

the workshop would be useful in their subsequent assessment practice. However,

13 % of the participants did not plan to use a scoring tool to assess the writings

of their EFL students.

The open-ended questions related to

the perceived changes in the assessment practices of teachers as a result of

the writing assessment training, revealed three major themes. The themes came from those teachers that: (1)

perceived their assessment as more objective after receiving the training; (2)

those that considered their assessment became more efficient in terms of speed

and practicality; and (3) those teachers that did not perceive any change in

their assessment practices as a result of taking the EFL writing assessment

workshop. The open-ended questions related to the perceived changes in the

assessment practices of teachers as a result of the writing assessment

training, revealed three major themes.

The themes came from those teachers

that: (1) perceived their assessment as more objective after receiving

the training; (2) those that considered their assessment became more efficient

in terms of speed and practicality; and (3) those teachers that did not perceive

any change in their assessment practices as a result of taking the EFL writing assessment

workshop. As to the reasons for considering that the use of rubrics made their

assessments more efficient, they affirmed that the perceived that their scoring

became more impartial.

…the rubrics provided in the workshop are useful to

supplement the rubrics we already used and to make a more objective assessment (TP04).

Another participant that considered that the workshop

contributed to a more objective view expressed the following,

…using rubrics to evaluate writing changed because

I managed to understand that when assessing a text, I must take into account

several things, not only spelling or grammatical errors. I also learned that with a rubric it is

easier for both, the teacher and the student, to be clear about the features of

writing that will be assessed and to ensure that the score awarded is reliable”

(TP302).

The second theme emerged from the participants who

considered their assessment became more efficient referred to the time invested

in assessing students work. The following extract of a trainee’s written comments

illustrates this view.

The use of rubrics has notably facilitated me the

assessment of students’ writing; it is a facilitating tool and it saves time (TP31).

Another teacher considered that after the training,

his assessment became more precise. The following comment reflects this view.

It’s easier for me to differentiate if a student

belongs to a specific grade of competence described in the rubric, without hesitating

or doubting when giving the score (TP36 ).

Most trainees that perceived no change in their

assessment practices after receiving the training reported that the rubrics

provided in the workshop were very similar to those they were already using in

workplaces (TP14).

One teacher perceived that the training received was

more useful to analyze his own use of rubrics than to assess his students’ EFL writing

(TP35).

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the perceptions that 48 EFL Mexican

university teachers regarding a writing assessment workshop. It also examined

the teachers’ perceived changes in their assessment practices after attending

the writing assessment training. Findings indicate that they perceived the

training as useful and practical. They also considered the training resulted in

a more efficient and objective assessment practice, as well as an easier and

less time-consuming scoring of students’ written work. Interestingly, a large

part of the sample considered implementing scoring tools in their classroom

assessment after the training, thus making a change in their assessment

practices. These results seem to echo those of Nier, Donnovan and Malone (2013) in which 35 language teachers

answered a post-training questionnaire. Still, four teachers disagreed and

strongly disagreed with the statement that training was useful for their

assessment practice. They also perceived that training did not change their assessment

practice. However, this study focused on their perceptions of their practice and

not on what they in fact do in the classroom.

Future research could focus on the concrete assessment

processes that they make happen in the classroom, to give them a better assessment

preparation. The majority of the EFL teachers who took the assessment workshop seemed

to be conscious of their language assessment weaknesses. They were always

willing to participate in pair and class discussion, and to practice the use of

holistic and analytic rubrics. However, a small group of teachers seemed to

refuse the use of scoring tools in their writing classes.

This finding seems to be related to their specific teaching

experience and professional backgrounds. The participants of this study, as foreign

language teachers worldwide, come from different professional fields, which may

influence their understanding of assessment. Jeong

(2013), found significant differences in the content of assessment training

courses depending on the instructors’ background.

The influence of language assessment trainees on the

ways they perceive assessment would need further research. Finally, this study

involved two data-collection instruments that involve indirect contact with

participants and favor short responses. Future studies could consider the use

of other collection instruments, such as face-to-face or stimulus –recall interviews,

which allow direct contact and more nourished responses.

CONCLUSIONS

The conclusions that emanate from this study highlight

the importance that writing assessment training represents for the language

student, the language teacher and for any type of language institution. On many

occasions, the future of a language student is determined by scores provided by

a teacher in the classroom or on a large-scale test. Teachers in the Mexican

EFL context on the other hand, are required to assess language skills on a regular

day-to-day basis. Therefore, it seems rather unfair for the student and the

teacher to conduct these assessments without prior and proper training,

jeopardizing the validity and reliability of assessment and the students’

future academic life. On the other hand, the results of this study could also

serve teacher trainers and language program managers or coordinators to

understand the needs of their teachers and their views in terms of writing

assessment. This with the purpose of comparing and contrasting them with the

institutions’ teaching goals and teacher training possibilities so that

appropriate sessions are provided, making the breach between the teacher and

assessment literacy as small as possible.

REFERENCES

Bailey, K. M. and Brown, J. D.

(1996). Language testing courses: What are they? In A. Cumming and R. Berwick

(Eds.), Validation in language testing (pp. 236–256). UK: Multilingual Matters.

Bailey, K. M. and Brown, J. D.

(2008). Language testing courses: What are they in 2007? Language Testing.

25(3): 349-383.

Bachman, L.F. and Palmer, A.

(2010). Language Assessment in Practice. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

Barkaoui, K. (2007). Rating scale impact on

EFL essay marking: A mixed-method study. Assessing Writing. 12(2): 86–107.

Barkaoui, K., (2011). Effects of marking

method and rater experience on ESL essay scores and rater performance.

Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice. 18(3): 279–293.

Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark,

V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research

design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J.W. (2015). A Concise

Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage

Publications.

Crusan, D. (2014). Assessing writing. In

Anthony John Kunan (Ed.) The companion to language

assessment (pp. 206-217). UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Council of Europe (2002). Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and

Assessment. Strasbourgh, France: Council of Europe.

Council of Europe (2009a). The

manual for language test development and examination. Strasbourgh,

France: Council of Europe.

Council of Europe (2009b). Manual

for relating language examinations to the Common European Framework of

Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching and assessment. Strasbourgh,

FR: Council of Europe.

Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Questionnaires in

second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in

applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methodologies. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. and Taguchi, T. (2010).

Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration and

processing. NY: Routledge.

Eckes, T. (2008). Rater types in writing

performance assessments: A classification approach to rater variability. Language Testing. 25(2): 155–185.

Esfandiari, R., Myford,

C. (2013). Severity differences among self-assessors, peer-assessors, and

teacher assessors rating EFL essays. Assessing Writing. 18(2): 111–131.

Fulcher, G. (2012). Assessment Literacy

for the Language Classroom, Language Assessment Quarterly. 9(2): 113-132.

González, E.F. (2017). The

challenge of EFL writing assessment in Mexican Higher Education. En Higher Education English Language Teaching and Research

in Mexico (p. Grounds & C. Moore, Eds.) (pp.73-100). British Council:

Mexico City.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2003). Writing

teachers as assessors of writing. In Kroll, B. (Ed.) Exploring the Dynamics of

Second Language Writing (pp. 162-189). New York, USA: Cambridge University

Press.

Hasselgreen, A., Carlsen,

C., and Helness, H. (2004). European survey of

language testing and assessment needs. Part 1: General findings. Gothenburg,

Sweden: European Association for Language Testing and Assessment. Retrieved

from. [Online]. Available in: http://www.ealta.eu.org/documents/resources/survey-report-pt1.pdf.

Jeong, H. (2013). Defining assessment

literacy: Is it different for language testers and non-language testers?

Language Testing. 30(3): 345-362.

Lim, G. (2011). The development and

maintenance of rating quality in performance writing assessment: A longitudinal

study of new and experienced raters. Language Testing. (28): 543-560.

Malone, M. E. (2013). The

essentials of assessment literacy: Contrasts between testers and users.

Language Testing. 30(3): 329-344.

Nier, V. C., Donovan, A. E., and

Malone, M. E. (2009). Increasing assessment literacy among LCTL instructors

through blended learning. Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly

Taught Languages. (9): 105–136.

Nunan, D. (1992). Research methods in

language learning. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Pavlenko, A. (2007). Autobiographic

narratives as data in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics. 28(2): 166-188.

Stiggins, R. J. (1995). Assessment literacy

for the 21st century. Phi Delta Kappan. 77(3):

238-245.

Stoynoff, S. and Coombe,

C. (2012). Professional development in language assessment. In Christine Coombe, Peter Davidson, Barry O’Sullivan, Stephen Stoynoff (Eds.) The Cambridge guide to second language

assessment (pp. 122-130). NY: Cambridge University Press.

Weigle, S. C. (2007). Teaching writing

teachers about assessment. Journal of Second Language Writing. 16(3): 194–209.